One of the most surprising aspects of the modern combat pistol is that it has managed to survive into today’s military world. Over the last fifty years or so, numerous attempts have been made to ‘finally’ acknowledge the limitations of the service pistol and consign it to the dustbin of small arms technical history, and yet it has survived. Indeed, today it thrives in numerous forms, still the object of the small arms designer’s art and the end pro duct of a great deal of production effort.

Exactly why the pistol has survived is fairly easy to explain:

there is, at present, nothing to replace it. The numerous at tempts to replace the pistol with some other form of weapon have all come to naught. Perhaps the most extreme attempt was by the Americans during the Second World War. Acknowledging that their service pistol, the .45 M19 11, was of doubtful com bat or any other value, except in extreme cases, the American military authorities developed the weapon that became the Ml Carbine. Ml Carbines were churned out by the million, but they never did replace the Ml 911. That venerable automatic continued to serve on despite them, and does so to this day, while the Ml Carbine has long since been declared obsolete by most military organizations and is now regarded merely as an odd dead-end of weapon development.

cp-1-7: The venerable Colt .45 MI9IIAI, the pistol destined to be replaced,

in time, by the Beretta Model 92F, the M9.

The same fate has not yet befallen the sub-machine gun. When the sub-machine gun was introduced on a large scale during the Second World War, many military pundits saw it as a viable alternative to the pistol and issued the new weapons accordingly. The sub-machine gun has made considerable inroads into what had once been pistol territory, but the pistol has still managed to remain, with its rate of issue largely unchanged. The sub machine gun has instead developed into a weapon form in its own right.

One other anticipated threat to the pistol has also been con signed to the oddity bracket. That is the machine-pistol (or machine-carbine), which continues to appear in modern forms, as these pages will show, but is now seen as an odd hybrid lacking many of the attributes of the pistol or its larger relative, the sub machine gun.

Exactly why no viable alternative to the pistol has been developed requires several answers. Despite its general lack of power, a very short effective range, an inherent lack of accuracy other than in skilled hands, and relatively high unit cost, the pistol still has many operational and non-operational roles. These are largely dictated by the better points of the service pistol. It is small and light enough to be carried for extended periods without causing excessive bother to the carrier, and it can be carried relatively safely, also for extended periods, and can always be ready for immediate use.

Set against these attributes there are few defined operational roles for the pistol to play on the modern battlefield. These roles are nearly all confined to personnel who have to carry a pistol for the simple reason that they cannot carry any other weapon due to the nature of their duties. Two examples that immediately spring to mind are the drivers and other crew members of armored vehicles, who simply do not have the space to carry anything larger than a pistol. This has not prevented some armed forces from issuing sub-machine guns to armored and other vehicle crews, but many armies continue to use the pistol. The other easily-recognized category includes signalers and other specialists who have to carry heavy or bulky loads on their backs and thus have a very limited capability to carry anything larger or heavier than a pistol.

cp-1-9: Pistols par excellence, the SIC pistol range: from the back, the

P230 with another P230 in its holster; the central pistol is a P220 with

a P225 on the far right; the pistol in the foreground is a P226.

Another category is that 0 military police personnel, who often have only a limited capacity to carry weapons larger than a pistol or sub-machine gun when operating close to the front line. This leads us to what is probably the largest military pistol- using category, namely the guard duty and security unit personnel who have to carry Out their various duties away from operational areas and yet who still have to carry some form of weapon to defend themselves and their locality. Military police again come into this category, but there are also the various staff personnel at the many headquarters and logistic function points. Many armed forces equip such personnel with standard rifles but others have acknowledged that the drivers of trucks or combat engineer equipment have little space or freedom to carry a bulky service rifle with them at all times, and so the is issued instead.

It is with military police and security unit users that the pistol is perhaps at its best. Within many armed forces, the pistol strapped to a belt is a badge of the military policeman, and it is with such units that the pistol probably finds its most valuable military role. The pistol can be carried by such personnel for ex tended periods without undue worry, but it is always ready for immediate use if needed. Even in this role, the pistol’s limited range is often a drawback, but set against that, the pistol is better than no weapon at all. This role also highlights something that continues to remain one of the service pistol’s biggest assets. In many circumstances, both in and out of a military operational area, the very carrying or brandishing of a pistol imparts authority to the user. In this way the pistol acts as a badge for the carrier or handler, who can use it to impose his command on others. It is for this reason that many military police units carry pistols, as mentioned above, and why personnel in unfriendly rear areas continue to carry pistols at all times, both on and off duty. Their pistols act as a mark of authority, but they also impart a sense of security to the carrier. Even though the user may be the world’s worst shot, he still knows that he has a lethal weapon at his command and can use its potential should it ever be required.

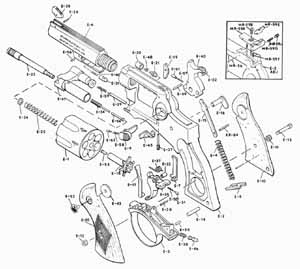

cp-1-10: Cut-away parts list of a typical modern revolver, in this case

the Ruger Police Service- Six, the numbers refer to spare parts.

The criminal (or terrorist) can also use the pistol for very similar reasons. By waving around a pistol when making demands, or using a pistol to impose his (or her) will on a situation, a criminal is only taking the ‘badge of authority syndrome’ one stage further, with the hapless victim(s) knowing all too well the consequences should they not be compliant.

The badge of authority syndrome is another reason why many staff officers continue to carry pistols, even though they may be unlikely ever to use them in a combat situation. Their pistol denotes rank and also provides a measure of self-assurance to the wearer. However, it is noticeable that few present-day high- ranking officers carry pistols once they reach front-line areas. In stead they are likely to carry a rifle or some such weapon, knowing only too well that snipers will be keeping an eye open for targets who appear to be in a position of authority; the wearing of a pistol often denotes a likely target.

Special forces continue to be one of the pistol’s more important operational users, no matter what form the special forces involved might take. One of the most conspicuous facts regarding special forces units, from frogmen to free-fall parachutists, is that they have to carry a great deal of equipment with them. That may leave room for only the pistol as a personal weapon. There are some special forces operational scenarios where the selection of a pistol will be the only possible course of action, and in some circumstances only a silenced model will suffice.

Other potential pistol-users include aircrew operating over hostile territory, as well as boat handlers in maritime or amphibious situations. But time and time again, compiling a list of potential pistol-users leads to rear area guard and security units. This in its turn leads us to civilian users and police forces.

No apologies will be made for including police forces in a guide dealing with the modern combat pistol. Nearly every police force in the world carries pistols at some time or another, and some carry pistols all the time. This may be seen as a reflection of the state of society in which people live or as a measure of the capabilities that law-breakers can draw upon to support their criminal activities. In some parts of the world the constant battle between the law enforcement agencies and law breakers has grown to a state of open warfare and to a point where lethal weapons are constantly in use by both sides.

For law officers, the pistol is the ideal weapon. Once again, the pistol’s small dimensions and light weight enable it to be carried either in an overt holster or concealed about the person, but ready for use at all times. The point was reached long ago where police officers had to attain a high level of pistol-handling skills to remain qualified to carry hand guns on duty. We are now at the point where many civilian police units can maintain a standard of all-round pistol proficiency much higher than the military personnel who might expect to use the pistol during combat on a battlefield.

Police forces must therefore overcome one of the pistol’s major drawbacks. It takes a long time to teach a recruit how to use a pistol properly and safely. Few military organizations have the necessary time to teach all potential pistol-users even the essential pistol basics, but most police forces, usually having only one type of weapon to deal with, can find time to divert officers to training sessions where pistol skills can be imparted or refreshed at regular intervals.

Needless to say, the pistol-manufacturing concerns have accordingly produced pistols specifically for police users, but while there are specialist police pistols (the ASP and the Heckler & Koch P7 pistols are obvious examples) the line between military and police pistols is becoming increasingly blurred. Many police forces simply utilize the standard service pistols used by their national armed forces. Others go their own way, but if there is a definite statement that can be made regarding any difference between police and military pistols, it is that until recently most police forces favored revolvers, while the military plumped for the automatic.

The difference between the revolver and the automatic was clear at one time during the automatic pistol’s development. The automatic was the more complex weapon of the two, was more prone to stoppages at awkward moments, often took time to bring into action and always required far more maintenance. That point was passed many years ago, and today the automatic is as reliable as the revolver, is as easy and rapid to bring into use as the revolver and requires no more maintenance either. We are now at the stage where the automatic pistol can be made smaller and easier to conceal or carry, and it is as safe to handle as the inherently safe revolver. One point where the automatic scores heavily over the revolver is in the amount of ready-use ammunition that can be carried in the weapon. Nearly all revolvers are limited by their cylinder dimensions to five or six rounds, but some automatics can carry up to 17 rounds (as with the Glock 17), plus an extra round in the chamber ready to fire.

cp-1-13: Revolver technology at its most extreme. This is the Ruger Super

Redhawk, a .44 Magnum revolver intended for the shooting enthusiast and

even the game hunter. This ex ample has a 241 mm barrel and a Ruger Integral

Scope Mounting.

All these advances in automatic pistol design have not led to the complete demise of the revolver. Hollywood is constantly reminding us that many American police forces, and especially plain-clothes operatives, still favor the revolver, whereas their European counterparts have for long favored automatics.

The last few decades have seen a dramatic improvement in the overall safety standards of the automatic. Many of the older automatic pistol designs embodied only token safety mechanisms, and were prone to go off if dropped or handled clumsily. The modern automatic pistol is a very different weapon that encapsulates all manner of ingenious methods of preventing unwanted firings. That has not meant that they have to be extensively fiddled with once they are needed in a hurry. Many of the latest pistols require no more preparation for firing after loading, other than simply squeezing the trigger in exactly the same manner as a conventional revolver. At all other times they can be carried holding a ready-to-use round already chambered, in complete safety, with only the human factor remaining as a safety hazard.

Along with the improvements in safety devices, the modern combat pistol has seen some other recent changes. One obvious change has been in the ammunition fired. At the turn of the century, virtually every new pistol introduced on to the market had its own specific caliber, and could fire only the ammunition that was produced for that particular model. Time, experience and commercial impositions have gradually whittled away the array of calibers and ammunition types, to the point where today only a few remain.

Of those few, one caliber and ammunition type is dominant; the 9 x 19 mm Parabellum cartridge. It is not a new cartridge, having started life back in 1902 when it was developed to be the ammunition for the famous Luger pistol*. Gradually the use of the 9 mm Parabellum round spread, to the point where it is now the universal pistol cartridge of the Western bloc. Even the American armed forces have decided to adopt it in place of their equally venerable .45 ACP (Automatic Colt Pistol) although it will be a very long time before the .45 cartridge is finally laid to rest.

The almost universal use of the 9 x 19 mm Parabellum cartridge should indicate that the term 9 mm Parabellum denotes some form of standard. In broad terms this is true. The 9 mm Parabellum is a standard NATO cartridge, and strict standards are laid down regarding dimensions, materials, and so on. However, these standards are more often used as guidelines only; many manufacturers deviate from the standards a great deal. Thus there are 9 mm Parabellum cartridges and 9 mm Parabellum cartridges. There are 9 mm Parabellum cartridges that use propellant loads that are definitely ‘hot’, and firing them will stress some pistol frames to their limits. Others are decidedly underpowered and will not function reliably and consistently in every make of pistol. Some use metal- or nylon-jacketed bullets, while others are bare lead. Some bullet noses are blunt, others are streamlined, and some manufacturers produce bullets with hollow points. Even the cartridge cases vary from thin light alloy to more substantial brass constructions. The overall quality standard might vary from the barely adequate to the excellent.

The variations are introduced by many factors. One is very obviously price. Quality ammunition costs money, and some manufacturers cater for the lower end of the market for the simple reason that they lack the technology to produce anything better; others are quite the opposite. There is also the factor that 9 mm Parabellum cartridges are not produced solely for pistols. They are also used in sub-machine guns.

* The Luger is not included in the scope of this guide, as it cannot be said to fall in the category of “modern” combat pistols. It is still in production, but only for the benefit of collectors and enthusiasts.

Generally speaking, 9 mm Parabellum rounds intended for sub-machine gun use are better made and have more powerful propellant loads, making their employment in pistols a somewhat risky business. Some manufacturers go to the length of producing armor-piercing or semi Parabellum rounds for use with sub-machine guns. Such cartridges, again speaking generally, should not be fired from pistols.

Thus the 9 mm Parabellum cartridge cannot be regarded as a standard cartridge, even though at first sight it should be. There are too many variations, which is perhaps not so remarkable, considering the number of countries in which 9 mm Parabellum ammunition is produced. These vary from Greece and India to Finland and Egypt. Nine mm Parabellum ammunition is even produced behind the Iron Curtain, for both Hungary and Czechoslovakia manufacture 9 mm Parabellum for export sales.

cp-1-15: The Colt Delta Elite, a rework of the old Colt MI9IIAI Government

Model to accommodate the 10 mm Auto cartridge.

The 9 mm Parabellum cartridge is primarily a military round. Police forces tend to favor slightly less powerful rounds, for in many police situations the extra power is not required or could even be undesirable (e.g. by penetrating walls and causing casualties to innocent bystanders). Thus calibers such as 7.65 mm and 0.38 are still widely used by many police forces. This has not prevented the introduction of super-powerful cartridges and weapons to fire them. The super-powerful cartridges include the Magnums in calibers such as 0.357, 0.41 and 0.44, but they were not developed primarily for police users or the military. They were developed via another route, the pistol enthusiast.

The pistol enthusiast is a complex beast who varies from the target shooter who loads his own ammunition to the information ferret who has no desire or opportunity to actually own a gun. They are a sizeable market, even for the large pistol producers, for however many restrictions are placed upon pistol ownership, as they are in many countries, there are still enough pistol enthusiasts willing to pay for the pleasure of actually owning and firing a pistol. Therefore manufacturers produce pistols and ammunition for them.

All manner of pistols are produced to cater specifically for the sporting pistol enthusiast, with ‘sporting’ a term that covers a wide field which varies from small caliber single-shot pistols, used for what the Americans call ‘plinking’, to massive bolt-action hand guns firing rifle ammunition and used for big game hunting. Few pistols used by such enthusiasts fall into the combat pistol category, as do even fewer of the highly refined and expensive target shooting pistols.

cp-1-16: One of the yen latest Ruger revolvers, the Ruger GP-100 .357

Magnum. This revolver has cushioned grip panels that are anatomically designed

to sit well in the hand, and the ejector shroud under the barrel is elongated

to make the pistol slightly muzzle to produce a steadier hold.

That still leaves the shooting enthusiast who devotes his spare time to handling and firing combat weapons. Few of them ever expect to use their treasured pistols against anything other than paper targets. For many of them, the firing is only an adjunct of their pastime. They are interested in the technical aspects of combat pistols, and that means everything from delving into the finer points of muzzle velocities and muzzle energies, to determining the optimum shape of a butt grip. Others, including those who may never even handle a gun, become involved in historical points or gathering information on rare sub-variants. There is also a very wide band of pistol enthusiasts who simply want to own or make the biggest bang possible.

This is the realm of the hand-loaders. Since few can aspire to actually manufacturing their own hand guns (although home modifications are another matter) the only alternative is to hand load their own ammunition. This activity can be as harmless as attempting to keep down shooting costs, while for others it means attempting to pack as much propellant into a cartridge as is feasible without causing the pistol involved to explode when fired. The hand-loading section has grown considerably over the years, especially in the United States where commercial ammunition producers eventually found it worth their while to pro duce the super-powerful Magnum cartridges, and pistol manufacturers produced pistols (usually revolvers) to fire them.

It was not long before police forces found the Magnum pistols to be very useful weapons - but only in trained hands. Firing any of the Magnum cartridges is something of an experience. The muzzle blast is prodigious, the flash can be severe and the recoil is considerable. The effects of what are often blunt-nosed bullets on a target are dreadful: even a peripheral hit on the human frame will produce traumatic effects that can cause severe shock and internal damage. The Magnum rounds are not to be trifled with.

Military use of Magnum rounds has been largely confined to police and security forces. Placing such weapons in the hands of barely-trained military personnel would be counter-productive, not only in safety terms but in the reactions of trainees to the awe-inspiring firing noise and recoil. Many American servicemen still speak in awe of the day they first encountered the .45 M191 1 pistol during their basic training. Many will freely admit that they were terrified of the things, and still are. Some manage to overcome their initial apprehensions and proceed to learn how to handle the M191 1 and other pistols properly -- others do not.

Nine mm pistols are scarcely less awe-inspiring, but, generally speaking, they are easier to handle and are effective enough for most military purposes. The 9 mm Parabellum round, despite having a lighter bullet than the old .45 ACP, manages to have better penetration powers and produces enough energy to make targets alter the nature of their activities. It also has a considerable range. Despite operational ranges being short (25 meters is usually regarded as the upper combat limit, although really skilled shots can expect to hit a human-sized target at 200 meters five times out of ten) the 9 mm Parabellum bullet is capable of inflicting wounds that could be fatal, out to a range of 2,000 meters or thereabouts.

Yet there are still those who want to go one better. Once again, the American pistol enthusiast has been busy seeking that something extra, and two new super-powerful cartridges have recently appeared on the scene. As yet, there are few pistols that can fire them, but some are imminent.

One of these new cartridges is known as the 10 mm Auto, which appears to have everything — more muzzle energy, a higher muzzle velocity, and so on. What it does not appear to have is a viable military future, for it is another of those rounds that is simply too powerful for the task. The 10 mm Auto has entered the realm of pocket artillery, and while there are pistol enthusiasts for whom the 10 mm Auto will act as a form of Holy Grail, there are few military users who will even contemplate the introduction of a new super-powerful cartridge, when existing cartridges are doing all that is required, to say nothing of procuring new weapons to fire the new ammunition.

To date, there have been few pistols available to fire the 10 mm Auto. There is a series of automatics known as the ‘Bren Tens’ that are obviously produced for the enthusiast, but the only remotely large-scale production to date has been of a variant of the old Colt M 1911, sold under the Colt label as the Delta Elite.

A more viable cartridge can be seen in the form of the .41 Auto Express. The design of this one has been far more carefully thought out, and the overall dimensions of the bullet and cartridge case are almost identical to those of the 9 x 19 mm Parabellum - the case is marginally longer. Thus to produce the new cartridge on existing machinery would not involve many changes, and the same can be said for the weapons that fire the new round. To convert an existing pistol to fire .41 Auto Express, modifications need be made only to the barrel, magazine and possibly the sights. That is quite a different prospect from having to procure an entirely new pistol.

By all accounts the .41 Auto Express appears to have a bright future. A version of the Israeli Desert Eagle has already been produced to fire the new round, and other pistols are on the way. Whether or not the military will find the .41 Auto Express a viable round remains to be seen, but it seems unlikely. The 9 mm Parabeflum is so well entrenched that it will take an extraordinary ammunition innovation to make any form of impact on military procurement circles.

Included in this guide is a cross-section of modern combat pistols. It is not an encyclopedia of the genre, for to attempt that would take years and the end result would still be incomplete. The most important message of this guide is that the modern combat pistol is alive and kicking, to an extent that continues to confound the prophets and pundits who pop up every now and again to declare that the combat pistol is obsolete and should be done away with. Every year new pistol models appear, new ammunition is devised, and all the while old models are updated and modified into new forms and for new markets. It all makes for a fascinating subject for study, and a rewarding one.

No one can ever think that they know everything about modern combat pistols. We can only go on researching and learning more about combat pistols every year.

« • Glock 17 »