When Roy Walford was just a boy, he figured out

that science could fix his biggest complaint: Life is too

short

DISCOVER Vol. 21 No. 02 | February 2000

|

Walford believes a draconian diet will postpone

the day when he has to seriously contemplate his own

mortality. Even though a nerve disorder makes it

difficult for him to walk from one end of his Venice,

California, apartment to the other, he hopes to live

another half century. “If I don’t, it doesn’t prove

anything,” he says. “It’s like doing an experiment on

one mouse.” |

Venice, California, is as good a place as any to stay young

forever. The sun shines 11 months a year, the temperature

never strays too far from perfect, and the famous (or

infamous) boardwalk is home to more than its share of

eccentrics, surfers, bikini-clad roller skaters, and body

worshipers. Roy Walford, professor emeritus of pathology at

the University of California, Los Angeles, School of Medicine,

would have to be considered one of the eccentrics, although he

manages to stand out even among the denizens of Venice Beach.

Walford lives in a one-story, redbrick industrial

building, one block from the beach. The windows are boarded

over. The entrance is in back, off an alleyway, through a

wrought-iron gate. Inside, Walford waits behind his desk with

a shaved head and a dramatic Fu Manchu mustache of the kind

more commonly seen adorning the members of outlaw motorcycle

gangs than scientists.

For Walford to

seem out of character is hardly new. This is not a person who

has led the closeted life of an academic or buried himself in

a laboratory, despite the obsession with which he has pursued

his science. For the better part of 50 years he has dedicated

his life and his research to the belief that threescore years

and fifteen is woefully short for a human life span and that

we should all live decades longer. And he’s had some success.

His most important work has focused on the relationship

between eating and longevity. In a seminal series of

experiments beginning in the 1960s, Walford studied the effect

of depriving laboratory mice of calories and discovered that

the less they ate—within reason—the longer they lived. The

research convinced him that it might be worthwhile to apply

the same lessons to himself. So since the early 1980s, he has

followed what he describes as a near-starvation diet. Walford

believes that his diet of a mere 1,600 or so calories a

day—about a third to a half less than a man his size would

normally consume—will give him the best possible chance of

living to 120.

And this is where the problem comes in. Here Walford sits

at age 75, still doing research, working on half a dozen

projects simultaneously, and yet he finds it difficult to

walk. A chronic nerve disorder he picked up nearly 10 years

ago as a volunteer guinea pig in a surreal ecosystem

experiment makes living to 120 seem an even more ludicrous

goal than it was back when he was able to walk normally.

While Walford’s condition has impaired his balance and his

mobility, his will seems unaffected: “I have to try to walk

consciously instead of unconsciously. Conscious walking means

you balance on one foot and then the other and you fall

forward.” He says this quietly, with precise, controlled

gestures, as if saving energy for the next decade. As one

might expect of a man with this kind of willpower, he is thin.

But at 5 feet 8 inches and 134 pounds—some 15 pounds less than

he weighed as a college wrestler—he still has a muscular

physique, the product of every-other-day weight workouts at a

local gym. And his nerve condition has certainly not kept him

from his goal of understanding aging. He visits his ucla

laboratory a few times a week to work on a “crucial

experiment” he hopes will give him an immunological answer to

postponing the toll of time.

Walford’s new research is based on the fact that in mice

and humans, the immune system malfunctions during aging,

losing the ability to distinguish between healthy cells and

invasive pathogens such as bacteria and viruses. Eventually

the system begins to mount so-called autoimmune attacks

against the body itself. Walford has long theorized that this

is a root cause of the regrettable side effects of aging, and

he still hopes to find out if he’s right. To test the theory,

he is raising mice with defective immune systems in an

ultraclean environment. “In a normal environment, they’d just

die of infection,” he says. “But I want to see if they have

correspondingly less autoimmunity and how that influences

their survival in a world without pathogens.”

If the mice live longer, Walford will have provided

formidable support to his immunological theory of aging, which

might have dramatic benefits for future generations. After

all, as he has pointed out, if human aging were completely

preventable, and disease eradicated, the average life span

might be about 300 years. Everyone would eventually die from

accidents, but those who are lucky might live to be 600.

Even as a youngster, Walford considered life entirely too

full of opportunities to imagine their fitting into one life

span. He grew up in San Diego, the son of a career naval

officer. He was the top student in his high-school class, as

well as a first-rate gymnast, wrestler and jitterbug dancer.

At 17 he announced in an article for his school newspaper that

the human life span was unacceptably short. As an

undergraduate at the California Institute of Technology, he

thought about studying philosophy, physics, and mathematics,

but settled on premed. “We used to joke that together we would

conquer three great challenges: space, time, and death,” says

his Caltech roommate, Al Hibbs, now a retired nasa space

scientist. “I was supposed to conquer space, Roy was supposed

to conquer death; together we would build a time machine. They

were young men’s fantasies, but he got interested in them

seriously.”

After graduation, both Hibbs and Walford went to the

University of Chicago—Walford for his medical degree, Hibbs

for a master’s degree in mathematics. There, Walford became

involved in theater and wrote his own comedic adaptation of

Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus. He picked up spare cash

performing in a balancing act, in which he was held aloft by a

biologist-cum-weight lifter. Before earning his M.D. in 1948,

he began practicing what he later dubbed his theory of

signposts. The essence of the theory is that life will become

an unmemorable blur unless people engage occasionally in what

Walford describes as “rather crazy” activities, which act as

signposts marking the passage of the years. In this case, he

and Hibbs made plans to sail around the world. They lacked

only the boat and the money to buy it with. So they decided to

play roulette.

“We figured the only way of getting money without having to

work at it was either to rob a bank or win at the casinos,”

says Hibbs. The two analyzed roulette tables, with the

knowledge that the tables aren’t mathematically perfect. “Some

numbers come up more often than they should,” says Walford.

They raked in $6,000 in Reno and $30,000 in Las Vegas, an

achievement heralded by Life magazine in an article headlined

“Two Student Theoreticians Invent System for Beating Roulette

Wheel.” Then they bought a yacht and set off on their sailing

adventure.

The plan was to cover the day-to-day expenses

for the trip by writing for Science Illustrated magazine. But

the magazine folded and, after 18 months of sailing, the duo

found themselves stranded in the Caribbean. So Hibbs

eventually returned to Caltech for his Ph.D., and Walford

headed to Panama for his medical internship. Following two

years at a veterans affairs hospital in Los Angeles and

another two at an Air Force pathology laboratory in Illinois,

Walford joined the medical faculty of ucla in 1954 and began

delving into the aging process.

Working with mice in the laboratory, he

quickly realized the benefits of the mantra of caloric

restriction research: undernutrition without malnutrition. The

maximum life span of a typical lab mouse is 39 months,

corresponding to 110 years in humans. Walford and researchers

have demonstrated that mice that eat only 60 percent of their

preferred diet will live as long as 56 months—the equivalent

of 165 human years—provided they start their diets before

three months of age. Although these mice are smaller than

their normally fed peers, they seem to retain their

youthfulness and intellects well into their extended old age.

“We’ve found that a 36-month-old restricted mouse will run a

maze with the same facility as a six-month-old normally fed

mouse,” Walford says. “That’s a substantial preservation of

intellectual function.”

SIGNPOSTS OF A

LIFE

|

Walford (above) motorcycled across

the U.S. in 1947; Right: Al Hibbs and Walford (in

glasses) used Reno roulette winnings to fund a 1949

sailing trip.

|

Left: Walford studied the body

temperatures of Yogis; Above: 1980s aging tests with

middle-aged mice led to his own drastic diet for

longevity. |

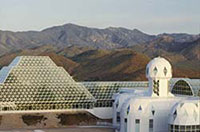

National Institutes of Health Institute on

Aging Web site has information on the physiology and

biochemistry of aging: www.nih.gov/health/chip/nia/aging.Find

everything you wanted to know about Walford and more, from his

experiences in the Biosphere to his diet plans to his books:

http://www.walford.com/. The Biosphere 2

homepage offers design plans, research projects, and visitor

information: http://www.bio2.edu/.

Walford’s dream of extending his own life span

became more tangible in the early 1980s, when he and his

then-student Rick Weindruch demonstrated that middle-aged mice

could also benefit from caloric restriction. Up to that point,

says Weindruch, now at the University of Wisconsin Medical

School, experiments by other researchers had involved sudden

caloric restrictions of obese young mice. One day the mice ate

to their hearts’ content; the next day they were on a strict

diet. The results, as often as not, were prematurely dead

mice. Weindruch and Walford took year-old mice and over the

course of two months eased them into a restricted-calorie

diet. The mice lived up to 20 percent longer than their peers.

The work persuaded Walford to severely cut his own caloric

intake. “Roy was toying with the idea before,” says Weindruch.

“This made him serious.”

Walford has kept to his starvation diet for

nearly 20 years. On a typical day, he has a low-fat milkshake,

a banana, some yeast, and some berries for breakfast. Lunch is

a large vegetable salad, and dinner is fish, a baked sweet

potato, and vegetables. His daily calorie count comes to about

half the 3,000 calories per day many Americans eat. Even Hibbs

lacks the wherewithal to try such an extreme diet. “It’s just

very difficult,” he says. “Damn few people, including me, are

willing to put up with it.”

The paradoxical aspect of Walford’s theory of

signposts is that some of them seem preordained to get in the

way of his personal pursuit of longevity. At age 48, for

example, he decided the time had come to attempt a wheelie on

his motorcycle while driving down Santa Monica Boulevard in

Los Angeles. He broke both his motorcycle and his leg when the

former fell on top of the latter. Two years later, he took a

sabbatical from ucla to spend a year walking across India in

“something like a loincloth,” measuring the body temperatures

of Indian holy men he met along the way. “I put a thermometer

up them,” Walford says. “You know, you can do whatever you

want on a sabbatical.” At 59, he decided to trek 2,000 miles

across Africa, from Dar es Salaam to Kinshasa, a

walking/hitchhiking/riverboat tour interrupted by authorities

in upper Zaire (Democratic Republic of the Congo), who accused

him of being a spy.

Walford managed to survive all these

signposts, only to be nearly done in by the one “rather crazy”

thing that had the gestalt of science: Biosphere 2, a huge

sealed greenhouse in the Arizona desert dreamed up by one John

Allen, an engineer, poet, and playwright who got the $150

million to build it from Texas billionaire Ed Bass. Biosphere

2 (Earth is Biosphere 1, say the Biospherians), covering more

than three acres of desert and 10 stories high, was hyped as

the most ambitious closed ecosystem in history. Walford’s

friend Hibbs, recruited for the Biosphere’s project advisory

panel, says Allen and his colleagues were surprised when

Walford agreed to join the crew. “They had trouble believing

that this rather active research physician at ucla was serious

about spending two years locked up in the Biosphere,” he says.

“I told them that I never heard him say anything like this

that he didn’t mean.”

|

|

LIVING IN A GLASS HOUSE:

Top Left: “We were on

display,” says Walford of his two-year stay in Biosphere

2 in Arizona during the early 1990s; Bottom Left: As

crew doctor, he hooked up Mark van Thillo for an

electrocardiogram; Below: as jack-of-all-trades, he

repaired an atmospheric sensor.

|

In September 1991, at age 67, Walford walked in with his

seven colleagues and the door was closed behind them. The

colleague closest to him in age was 40; the others were an

average of nearly 10 years younger than that.

It is characteristic of Walford that he

describes what happened next as “kind of a miracle,” despite

its lasting effect on his health. “I’d been working on caloric

restriction in animals for 20 years,” he says. “And when we

got inside, we found we couldn’t produce enough food to feed

us all. But what we did produce was very high in quality. So I

took advantage of that and told the people it’s nutritious and

it’s healthy, but you’re going to be hungry. They could elect

that food be sent in from the outside, or they could elect to

live on a healthy starvation diet.” The Biospherians went for

the starvation diet—vegetables and a half-glass of goat’s milk

every day, meat once a week—for two years. Walford might have

survived unimpaired had it not required what he describes as

an “ungodly” amount of work to keep the Biosphere going.

“Eight people running an entire mini-world, unable to call in

an electrician or a plumber or anything, anybody,” he says.

Six days a week, three hours a day, the Biospherians did heavy

manual labor in the fields. Walford was also responsible for

the functioning of 500 atmospheric sensors, many of which hung

from the rafters.

“I was climbing all over the structure,” he says, “and

it was physically exhausting and psychologically stressful.”

His weight dropped to 119 pounds. “I was

really emaciated,” he says. “And the workload kind of

destroyed my back.” A more insidious problem may have come

from nitrous oxide poisoning. Nitrous oxide is a gas released

into the atmosphere by the respiration of microorganisms in

the soil, but it is broken down into its harmless components

by ultraviolet light from the sun. The glass roof of the

Biosphere, however, blocked ultraviolet light, and the nitrous

oxide gradually reached concentrations 100 times that of the

outside world. “Long continuous inhalation is toxic,” says

Walford. “It knocks out the cells in the brain that have to do

with motion.”

Walford’s balance problems apparently started

in the Biosphere; he says he didn’t realize it at the time,

but he can see it now when he looks at himself in old

videotapes. The official diagnosis when he got out was

peripheral and central nervous system damage, and, despite

back and hand surgery, he has never been the same. Once he

starts walking, Walford can keep going in a kind of

slow-motion, joglike gait, but getting himself going is a

challenge.

‘It always seemed there were so

many things to do in life that the first thing to do was live

longer’

|

“I am in good shape for someone who

is 75,” says Walford, standing in the doorway of his

home office. Fitness machines are the main source for

his cardiovascular exercise. “Using a treadmill is

easier for me than walking because the motion is very

even,” he says. |

Walford’s

apartment, which he shares with Swami, a bluepoint Himalayan

cat, resembles a New York artist’s loft and is cluttered with

memorabilia of his life and travels, much of which seems

devoted to the female body. Hibbs, who recently paid a visit,

says Walford’s concern with living forever may be linked to a

“so many women, so little time” sensibility. Although married

for 20 years and the father of three children, Walford has

been single since 1972. “Now he likes to jump from woman to

woman quite frequently,” says Hibbs, “although they always

seem to be the same women. He keeps rotating among them.”

Walford says there may be some truth to the

so-many-women-so-little-time theory, but he prefers a broader

explanation: He has always had too many projects going at one

time, and women just happen to be a part of them. “It always

seemed there were so many things to do in life that the first

thing to do was live longer,” he says.

Among his projects is a book about the Biosphere that he

expects will take at least five years to complete. He’s also

working on a Biosphere documentary based on 80 hours of

videotape he took while inside. He’s collaborating with Natasa

Prosenc, a Fulbright scholar and a video artist. She’s the

expert documentarian, says Walford, but he’s taking a course

in multimedia and has built a “mini-postproduction studio” in

the room next to his office.

Once those projects are complete, further studies in

history or mathematics may be next. “I like them both,” he

says, “but I don’t know how I’d do as a mathematician.” The

uncertainty seems to entice him. The line on mathematicians is

that they do their best work before they hit 30, after which

it’s a downhill journey. “It would be interesting to try my

hand at mathematics,” he says, “because everybody assumes it’s

a young man’s trip.”

Meanwhile, he’s hoping the genetically engineered mice he’s

raising in a pathogen-free environment will help uncover more

secrets of the aging process. That, of course, harking back to

Biosphere 2, raises the obvious question: Would Walford live

in a hermetically sealed, pathogen-free plastic bubble, if

that’s what it would take to add 20 or 30 more years to his

life?

“Well, I’d do it for a while. Sure. I mean, look around

you,” he says, laughing and pointing to his windowless office,

living room, and video-art studio shut off from the outside

world. “I could live in here for a long time and keep pretty

happy doing all the stuff that I do.”