Home

Camera, lens & related electronics gear

Talking the talk

A HUNTING BINOCULAR can cost more than your rifle. It can also be worth

more to you because the hardest part of shooting big game is still finding

big game to shoot.

A top-flight binocular helps you find more game. Here’s

what the optical jargon means, and how to use it to sift binoculars.

Center focus: A center focus bin ocular has a center wheel

and one adjustment ring on an eyepiece (usually the right-hand eyepiece).

The advantage of this design is speed of operation. Once you set the

eyepiece, or diopter adjustment to produce a sharp image in concert with

the other (left-hand) barrel, you don’t have to adjust the eyepiece when

changing viewing distance.

The center wheel moves both barrels at once.

Some modern center focus binoculars have the diopter adjustment in the

middle — a companion wheel that can be moved independently of the main

wheel but “locks” to it when you want to focus both barrels at once.

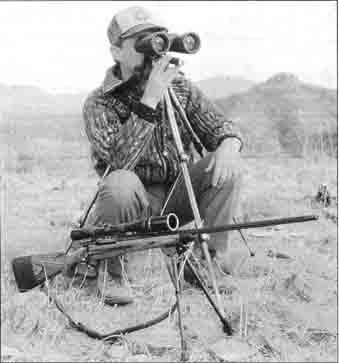

Fig so-3-28-0 Big binoculars benefit from a tripod.

Exit pupil: The diameter of the “window” you see in a binocular

barrel when you hold it at arm’s length, exit pupil is derived by dividing

magnification into objective lens diameter.

A 7x35 binocular has an exit

pupil of 5mm. That’s a good number. Smaller exit pupils don’t let enough

light through at dawn and dusk. Because exit pupil shrinks if you boost

power without increasing lens diameter, high-power binoculars exact a

price: Either you give up brightness or put up with a bulky, heavy instrument.

Exit pupils bigger than 6mm are unnecessary because your eye won’t dilate

any more in the dimmest of hunting light. Older hunters, with a more

limited dilation range in their eyes, may find that 5mm is a practical

maximum.

Eyepiece: Colloquially, the eye piece is the part of a binocular that you hold near your eye — the rear of the instrument. Each eyepiece includes an ocular lens. Depending on binocular design, it may also feature a focusing or diopter ring with registry marks on the ocular housing. Folding rubber cups or tubular sections that pull out or twist out on helical threads adjust eye relief (the distance of your eye from the ocular lens). If you don’t wear eyeglasses, you’ll want the cups extended. Angled eyecups block out peripheral light to give you a sharper, seemingly brighter picture.

Individual focus: An “IF” binocular has a focus adjustment on each eyepiece but no center wheel. Not as vulnerable to dust and water as is a center focus glass, it is inherently sturdy but slower to use. Whenever you want to change focus, you must do it twice, adjusting each barrel individually. Click detents and clear diopter markings on some modem binoculars speed the adjustment. With them, focusing becomes a bit like adjusting a riflescope for a more distant target.

Lens coatings: Around 1940, a Zeiss engineer discovered that a thin layer of magnesium fluoride reduced reflection and refraction at lens surfaces. Without coating, each air-to-glass surface can lose 4 percent of incidental light. “Fully coated” refers to all lenses, inside and out. “Multi-coated” indicates several coatings layered to enhance transmission of various wavelengths. Insist on fully multi-coated lenses. Don’t go by the color you see in a lens. There’s no “right” color of optical coating. Also, lenses can be tinted without being coated.

Objective lens: The biggest lens in a binocular, the objective is the front lens. It is not movable. Size of the objective has nothing to do with magnification or field of view. It does directly affect brightness and resolution. The bigger the glass, the bigger the exit pupil and the higher the values for relative brightness and twilight factor. Objective lens diameter in millimeters is the second set of numbers in a binocular designation (e.g., 7x35 signifies a glass of 7 power, with 35mm objective lenses).

Ocular lens: The ocular, or rear-most lens, in a binocular, is just one of many lenses assembled as a sys tem. The placement, size and surface shape of the ocular lens affect field of view and eye relief. Bright ness is not affected — unless, of course, the lens is not coated or is in some other way inferior to companion lenses. Eye relief (the proper distance of your eye behind the binocular) is measured from the rear surface of the ocular lens.

Porro prism: This traditional bin ocular design features offset or “dog leg’ barrels that offer a wider front lens spacing than roof prism models. There’s an advantage to this spacing: better distance perception. Porro prism instruments are bulkier than those of roof prism design, but not necessarily heavier. Image quality is independent of light path; both types of binoculars can deliver superior performance. Most porro prism binoculars are offset horizontally; however, vertically offset barrels have recently popped up in the market. Objective lenses bigger than 50mm are best used on porro prism glasses, because straight barrels won’t allow the ocular lenses to swing close enough together for normal eye spacing.

Relative brightness: A measure of light transmission, relative bright ness is calculated by squaring the exit pupil. Thus, while an exit pupil of 7mm is 40 percent bigger than a 5mm exit pupil, its relative brightness (49) is essentially twice what you get with the smaller “window” (25).

Resolution: Your optometrist’s chart tests your eye’s power of resolution. You want the highest resolution possible from a binocular, within practical confines of lens size and power. You’ll need to see detail — the tip of an antler, the glint of an eye, the curve of an ear — in a jigsaw puzzle of autumn color. Test resolution outside, where you can target tiny objects in shadow and glass obliquely toward the sun. What you see is what you’ll get afield. Twilight factor is a mathematical expression of resolution in dim light (square root of the product of magnification and objective diameter).

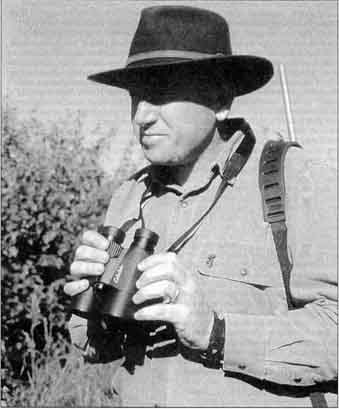

Fig so-3-29-0 Leupold makes binoculars for finding game and spotting

scopes for evaluating it.

Roof prism: Roof prism binoculars lack the “dogleg” profile of porro prism glasses because the light path is cleverly manipulated by a prism that bends the light within a more compact space. Light leaves along the same axis that it enters. But the roof prism splits the light down the middle as it enters, cleaving incident light into color bands that must then be brought back “into phase” to pre vent color fringing. Zeiss was the first to come up with a lens coating that brings exiting light back into phase. Now, other companies offer phase-corrected roof prism glasses. Color or phase correction is necessary only in roof prism binoculars. Roof prism instruments weigh about the same as (sometimes more than) comparable porro prism models.

Twilight factor: A measure of resolution in marginal light, twilight factor is mathematically the square root of [ multiplied by objective diameter]. So if you have an 8x40 binocular, the TF value is the square root of 320, or 17.9. Increase magnification to 10x, and the TF becomes the square root of 400, or 20 — while the exit pupil shrinks from 5mm to 4mm. The extra magnification more than offsets the drop in brightness. If you make the objective lens 25 percent bigger (50mm), the TF for an 8x glass is 20. For a 10x it’s 22.3. Once more, high magnification results in a greater TF value. You need a 25-percent gain in objective diameter to equal a 20-percent boost in magnification. So, while bright ness is an asset, reducing magnification to make the exit pupil bigger will not necessarily give you a higher twilight factor or better resolution in dim light.

Fig so-3-30-0 At dawn and dusk, a 5mm exit pupil is a practical minimum

in binoculars as well as riflescopes.

Fig so-3-30-1 Varmint hunters use binoculars to find distant targets

even if their rifles wear powerful scopes.

Sifting out a good binocular

When I was a lad, famous big game hunters like Jack O’Connor carried binoculars of modest size and power. I remember finally saving enough money to buy a 7x35 Bausch & Lomb Zephyr, one of the lightest popular glasses of the day, and one of the most costly. It was also among O’Connor’s favorites, and though it cost me a month’s wages second-hand, I was thrilled to get it. I’ve spotted more game with that binocular than with any other, and I’ve since bought a couple more used Zephyrs. The optics are bright and sharp, even by today’s standards. The frames are sturdy, and I haven’t found a binocular of comparable performance that weighs less.

My B&L 7x35 stayed in my kit long after better glass appeared on the market. When I fell on the rocks with it and cracked the jacket, I wrapped thin buckskin around the barrels and bound it in place with electrician’s tape. I bought for a friend a new porro prism binocular that was clearly superior. I carried the old 7x35 when the latest top- quality models were available on loan. I didn’t want to give up that glass! It was like a comfortable pair of boots that had given me too much service. I’d grown to like the binocular not for how it performed but for how many miles it had been with me, and for hunts, long past, that came to mind when I picked it up. I justified my fidelity with the reminder that when it was discontinued in 1958, B&L’s lovely Zephyr listed for $350. Only the best binocular could bring that sum when new automobiles left the lot for under $2,000!

But even the best gear reaches retirement age. I suspect that a few years from now, the best will be better than today’s best. Still, the evolution will remain slow, because top- end glass now transmits more than 90 percent of available light and delivers images so sharp as to challenge the resolving power of our eyes. A high-quality binocular doesn’t become obsolete in a decade. It makes no sense to wait for better binoculars to appear. As the fellow in the green trousers and pink tie on the car lot says, buy now!

But not before you shop. You have to know what’s available before you can make a good buy. Here are a few things to keep in mind.

Catalogs don’t always tell you all that you should know about a binocular. For instance, ad copy might specify “coated lenses.” Assume, then, that not all lenses have been coated. Even inside the body, every uncoated air-to-glass surface can still cost you brightness. Don’t be misled by the straw, blue, green or purple hue on the outside lenses of models with no internal coatings. What you want are fully multi- coated lenses. Color tinting, avail able on some inexpensive binoculars, does not enhance brightness.

Steiner uses a TJV lens coating on its Safari line of binoculars to cut glare and a green lens coating on its Predator series to filter the transmission of green color to your eye. The UV film protects your eyes in bright sunlight; the green coating enhances browns and reds so big game more readily pops out of green background. I don’t like tinted lenses because they reduce the amount of light my eye receives. At dawn and dusk, I want all the light to come through! Steiner Nighthunters have no such “block” coating.

Fig so-3-31-0 Birders insist on high resolution from their binoculars. Hunters should too!

Fig so-3-31-1 This Doctor Optic 30x80 is like two spotting scopes on

one tripod. It’s great for prolonged glassing!

You shouldn’t detect any difference between the images of porro prism and roof prism glasses of similar quality. But you might find one more comfortable than the other. I choose center focus binoculars over models with individual focus simply because they’re faster to adjust while I have the binocular to my brow. Avoid binoculars with no focus adjustment (“permanent” focus is a myth).

An increasingly popular feature is rubber armor. It’s a good idea, not only protecting the binocular but muffling the sound of it banging against rifle or rocks as it swings during a climb. Rubber gives you a sure grip with cold hands. You don’t need a thick rubber jacket, or one with a camouflage print. Rubber armor helps keep water out of your glass too, though it is not by itself evidence of waterproofing. I don’t insist that a binocular be waterproof A few are, but many models of the very best optical quality are not. I’ve yet to catch my binocular leaking, though I’ve often hunted in the rain. A binocular that doesn’t pass military submersion tests may never leak. As with boots, if waterproofing is important to you be sure you know the terms. Not every salesman who says “waterproof’ is guaranteeing to the same standard. Waterproofing, by the way, is not fog proofing. Nitrogen, introduced under vacuum, pre vents interior fogging.

When you compare binoculars, consider their feel and ease of operation. The focus dials should turn smoothly, but not so easily that they’ll turn accidentally if you brush them lightly. Detents or the click adjustments on some binoculars appealed to me at first, but after using them I’ve come to prefer binoculars without those stops. Invariably, perfect focus comes between the clicks. At least it seems to. A smooth turn of the wheel gives me a sharp image quicker. Remember that on a center-focus binocular, you won’t have to adjust the individual barrel often, if at all, in the field. You set that barrel, or the diopter, and the center wheel adjusts it in concert with the other barrel when you focus.

Traditional fold-down rubber eye- cups have given way to firm eyecups that pull out. Those that pull out with a twist are best because you can press them against your brow when glassing without having them collapse. Eyecups angled to block out sidelight help concentrate your vision in some light conditions.

Optical qualities are the most important feature of any binocular, but they’re seldom evaluated by the buyer. Partly that’s because a rigorous evaluation requires equipment and a knowledge of optics that few buyers have. But you can get a pretty good idea of how any binocular will perform in the field just by stepping out the door of the shop in the evening.

Fig so-3-32-0 Mid-size binoculars are the best choice for hunters in mountainous country like Montana.

Fig so-3-32-1 The best multi-coated lenses deliver a great advantage

when you’re glassing into light.

Outside is a must. Artificial light differs from natural light. Besides, you want to see how each product per forms when you’re looking into shadows and at an angle toward the sun. If you can’t test it in rain and thick mirage, you at least want to look at far-away targets. Check resolution by picking apart the detail you can’t resolve with your naked eye. It’s useful to bring a cardboard box with a resolution chart like the 1951 Air Force grid on page 27. You’ll then have a repeatable test that lets you assign numbers to each trial, and separate product by fineness of resolution. Check peripheral distortion by looking to the edge of the field. Look at billboards or fences with straight lines, and move the glass so they ease out of your field of view. Do lines stay straight? Corral a square object in the middle of the field. Do the sides stay straight? Move your eye slowly off- axis so a clamshell of darkness bites into the field. Are the colors welded in place, or do you see color? When you swing the binocular toward the sun (don’t target it directly!), what hap pens to the image?

Bear in mind that no binocular can deliver as much light as the amount that strikes its objective lens. If you get 95 percent, you’re getting a very bright picture. Why do some binoculars seem to gather light? They don’t, of course. An aperture or tunnel can make images seem brighter and sharper by blocking out peripheral light. My friend Bill McRae demonstrates this phenomenon with a pair of cardboard toilet paper spools fastened together and painted black, inside and out. A block in the middle maintains proper interpupillary distance. Looking through these spools, you’d think you were looking through optics. Everything appears brighter, with crisper detail. No wonder that unwary shoppers snap up cheap binoculars, thinking they’re a great buy! But next time you’re tempted, remember that toilet paper rolls are cheaper still.

At first, you’ll work hard to see differences between inexpensive binoculars and those that cost hundreds of dollars more. But eventually they will pop out. And then you won’t be able to ignore them.

It’s easy to be misled in binocular comparisons. You’d think that all 7x35s would have the same field of view, for instance, and if one had a wider field than another, you should choose it. But wide-angle binoculars are not always the best choice. A 400-foot field is more than you can study at a glance. Land sakes, you’re looking at the breadth of a high school football stadium! Even at distances under 1,000 yards, where field shrinks proportionately, it’s much bigger than you need. Commonly, binoculars with big fields show more edge aberration — image bending and “fuzzing.”

Incidentally, “wide-angle” binoculars are by definition those with an apparent field of view of 65 degrees or greater. Apparent field is determined by multiplying degrees times the power. A 7x binocular with a 9- degree field thus has an apparent field of 63 degrees and would not be classified as a wide-angle binocular. One degree equals 52.36 feet at 1,000 yards, so that glass would give you a field of 9x52.36, or 471 feet. It’s almost a wide-angle binocular, and may indeed give you a broader field than its competition.

(Riflescopes, because of their long eye relief requirements, become “wide angle” with narrower fields of view. A fixed-power scope is a wide-angle model if its apparent field is 26 degrees; variable scopes meet the standard at 23 degrees.)

Looking close

It’s late in the season. Hunters and worsening weather have driven animals to timber. You’ve watched enough meadows. Time to shed clothes and binoculars and prowl the thickets — right?

Yes and no. Certainly, to shoot game you must go where the game is! Layer off the long handles so you can move. But leave the binoculars? You might as well hunt with a card board box over your head.

Binoculars aren’t just to magnify distant game in open country. Good glass sharpens detail. And though a binocular cannot manufacture light, the best can seem to brighten the dark places where big animals lurk. A binocular makes you look deliberately, methodically. With it, you’ll find game.

Of course, using a binocular won’t guarantee that you’ll shoot game. I’m sometimes better at the finding than the shooting...

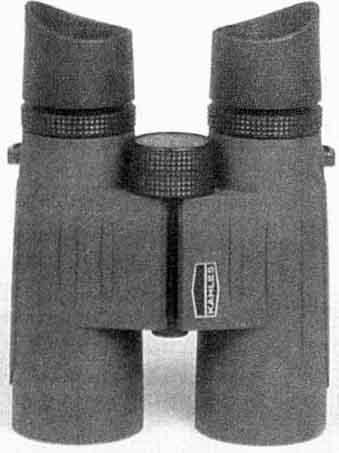

Fig so-3-33-0 Cabela’s Alaskan Guide binocular delivers a crisp

image at a modest price.

We slipped off the rim and sneaked along an elk trail threading into the shadows. The urine-stale duff beneath the Douglas firs had been churned to muck by elk traffic. We moved quietly despite our brisk pace. The bull had been vocal, but this late in the morning he might quit braying any time.

Everything around us got dark and cool, and elk smell came feedlot strong. I slowed. Ken kept tight behind me. The muzzle of his .300 bobbed ghostlike alongside my ear.

Elk don’t always do what you think they should, and when this bull doubled back he nearly caught us moving. But I saw the antler tips slide against the blackness, like a squadron of white wasps dipping in unison. I stopped abruptly, and Ken braked so close I could almost hear his heartbeat. In a second, the legs came into an opening, then the glint of an eye and a great neck the color of a burnt steak. My binocular was suddenly at my brow. The bull came on, filling the field.

If you haven’t been really close to a really big bull elk, you can no more imagine it than you can imagine rocketing along a racetrack if you haven’t driven a very quick automobile. There’s a presence that only old bulls have, a sense of urgency other elk can’t evoke. This stud moved like a Hereford bull as he approached, almost slouching between the rhythmic bunching of those great hams and shoulders. He had the easy rolling, arrogant gait of an athlete with more muscle than he needs to walk but supremely aware he can use it explosively whenever he chooses. The head sagged and weaved almost drunkenly but in a deft, practiced effort to pilot those eye-popping antlers through the brush. Then he stopped. I reckoned he stood about 18 steps away.

What followed was, I concluded later; a prime example of what not to do on an elk hunt. Oh, I didn’t make any of the really stupid mistakes, like move. Or yell, “Shoot, Knot- head!” In fact, I made no mistakes at all because I didn’t do anything except try to corral that truck-width bone in the field of my glasses so I could score it accurately and whisper calmly to the hunter beside me that yes, this was indeed a fine bull and that he should consider giving him a Nosler.

But no decision is always a decision. And doing nothing can damn you as effectively as inactive bungling. I found, after a couple of milliseconds, that I couldn’t possibly score that bull. There was too much antler too close, and much of it hid den by the enormous front tines. The elk was staring our way, waiting for our scent to pool. I wanted desperately to hear the .300 but couldn’t bring myself to give the signal. Six-point elk in thickets all look bigger than they are. Most shrink several sizes as they drop.

I watched as the tide crawled to his nostrils and he swung that huge rack around. Too late I saw fifth points as long as rolling pins and thick beams that hooked down along the last ribs.

“We’ll find another,” I whispered when he was gone. Ken said nothing. “He probably wasn’t as big as he looked.” I grinned weakly. Ken said nothing again. “It’s always best to pass ‘em up when you can’t get all the antler in the binocular,” I added, feigning logic. “Besides, you don’t want to quit now.”

Ken was still staring saucer-eyed after the bull when I turned to walk briskly back up the trail. At this point, I just hoped he would not shoot me.

You can’t buy a binocular that will stand in for good judgment. I decided as we climbed, though, that I could easily have handicapped myself with a binocular designed for long-distance hunting. Most binoculars are made for looking long because that’s what lots of hunters think they should be doing with bin oculars. High-magnification glass is becoming more popular as riflemen look primarily for game in the open where they can shoot it deliberately and from a solid position with their flat-flying bullets.

I’d been using my old Bausch & Lomb 7x35 Zephyr; a lightweight glass with a field big enough to find game quickly and frame any elk rack (almost). A glass like this is still an ideal pick if you hunt where most animals live and not where most hunters think they should live to accommodate benchrest shooting styles. Except for pronghorns and caribou, most North American big game is shot in or near woody cover where high magnification can get you in trouble.

Though 8x and 10x binoculars have become popular of late, the 7x is still a fine all-around choice. And Gx glass is adequate for most hunting. In the timber, it’s hard to beat a 6x30, a compact instrument with a 5mm exit pupil. My friend Bill McRae has an old Zephyr 6x30. Old is what you’ll have to look for these days if you want any 6x30. Like low-power, fixed-power riflescopes, they’re victims of a public so enamored with high power and big glass that utility often drops out of the equation.

It’s important when glassing to know what you’re seeing. Up close in thickets, you need a wide field of view to get the whole picture rather than an undecipherable dollop of brush. You want great depth of field to keep everything in perspective and so you don’t have to refocus your binocular often. You can also use a big exit pupil to keep images bright under shadow. These are the attributes of low-power glass.

Fig so-3-34-0 High resolution only matters (f you can hold a binocular

still.

All that became clear to me years ago when I was inching through dense riverine alders in Oregon. I knew two deer had entered this patch, and I moved very slowly. Midway through I stopped, convinced that if the deer had not sneaked out, they were close enough to see. My world became the drab latticework of branches inside my binocular field. I held the glass still and mentally picked the branches apart. Then I moved the barrels slightly to the right and began again to disassemble. I’d come to doubt the wisdom of this tedium when suddenly a white spot appeared in the field of my 7x35 Bausch & Lomb. I let my eyes work inside the glass. The spot became the throat patch of a doe. A branch behind her became an antler. My bullet hit the buck below the eye, my only aiming point.

If you’re hunting without a binocular, you’re hunting handicapped. So, too, if you move it when you’re looking (notice how deer stand statue-still when looking for you?). When you take glass into the places where big game lives, use it often and deliberately. Remember that at ranges measured in feet, any animal you see will be close enough to detect you. Indeed, odds are that any game you see will already be aware of you and ready to catapult away. Your job is not to see a buck before he sees, hears or smells you. That’s a great line but so difficult as to be impractical. No, your real job is to spot the animal before it thinks you can see it. In a thicket, game will commonly stay put until discovered. Spot a piece of the animal while you’re still so well-screened that you’re not an immediate threat, and you may get a shot. Naturally, when you do see antlers, you pretend that you don’t, moving casually and slowly and keeping your gaze averted until you’re looking through the sight at the vitals.

Fig so-3-35-0 Kahles 8x42 and I 0x42 roof prism binoculars are marketed

in the U. S. by Swarovski.

Fig so-3-35-1 Weaver’s Grand Slam binocular is reportedly a reincarnation

of the excellent Simmons Presidential.

Fig so-3-35-2 Minox, a Leica brand, has expanded its line of mid-priced

roof prism binoculars.

But that’s the finale. First you must find the beast. Here are some tips:

Power down. Stay with 7x glass — 8x at the most. More powerful optics are harder to hold steady without a rest. Also, the lower the power, the bigger the field of view and greater the depth of field. Field is especially important up close because, while its angular measure is the same as when you’re looking far, the actual window is much smaller. A wide field helps you quickly find some thing you spotted with your naked eye, and to see more without moving the glass.

Consider convenience. Glassing helps most when you glass often. Choose a binocular that’s easy and comfortable to use. Center-focus models are my pick because pressure from one finger can sharpen the image instantly. Sliding, twist-out and collapsible rubber eyecups all work, but I like twist-outs. They’re quick, and they stay put. Waterproof models make sense in rainy places. Thin rubber “armor” is also an asset. It provides a sure grip and won’t make noise when slapped by brush or bumped by your rifle. Make sure the binocular focuses as close as you’ll want to look.

Get small, but not too small. You’ll want a binocular that stows inside your jacket front, a glass light enough to carry easily. But tiny lenses won’t deliver the brightest images. Remember that exit pupil, the diameter of each shaft of light visible in the lenses with a binocular at arm’s length, is a good measure of brightness.

Buy quality. Looking close doesn’t mean you can make do with substandard optics. If you miss the glint on a buck’s nose, you may have missed the deer of a life time. Superior glass is costly, but you can get the fully multi-coated optics responsible for bright, sharp images without selling your first born into slavery. Shopping the used markets, you’ll keep a lid on prices and perhaps turn up a discontinued glass that’s just right for your woods hunting — like B&L’s 6x30 Zephyr.

Here are a few binoculars that make sense for tight places, where game is alert and short shots are the rule. These models are also excellent all-around birding and hunting binoculars, contrary to what you might hear from people enthralled by bigger glass. A bright 8x binocular gives you all the magnification you can hand hold easily, and enough to sort out wing primaries at reasonable yard age, or pick an antler tip from a tangle of deadfall. (rp = roof prism, pp = porro prism.)

Fig so-3-36-0 Swarovski’s 7x50 SLC delivers more light than your

eye can use under normal field conditions.

Make/Model/Description |

Field ( ft. 1000yds.) |

Weight (oz.) |

Retail Price |

Bausch & Lomb Elite, rp 8x42 Bausch & Lomb Discoverer, rp 7x42 Bausch & Lomb Custom, pp 8x36 Brunton, rp 8x32 Burns Signature, rp 8x42 Burns Fullfield, pp 8x40 Bushnell Legend, rp 8x42 Cabela’s Alaskan Guide, rp 8x42 Cabela’s Waterproof, rp 8x42 Kahles, rp 8x32 Kahles, rp 8x42 Leica Ultra Trinovid, rp 8x32 Leica Ultra Trinovid, rp 7x42 Leica Ultra Trinovid, rp 8x42 Leupold Wind River WM, rp 8x32 Leupold Wind River W2, rp 8x42 Leupold Wind River, pp 8x42 Minox BD, rp 8x32 BR Minox BD, rp 8.5x42 BR Nikon Venturer LX, rp 8x42 Nikon Superior E, pp 8x32 Nikon E2, pp 8x30 Optolyth Alpin, pp 8x30 BGA Optolyth Alpin, pp 8x40 BGA Optolyth Royal, rp 8x45 BGAIWW Pentax DCF WP, rp 8x32 Pentax PCF V, pp 8x40 Sightron SIT, rp 8x42 Steiner Nighthunter, pp (mdiv. focus) 8x30 Swarovski EL, rp 8.5x42 Swarovski SLC, rp 8x30 WB Swarovski Classic Habicht, pp 7x42 MGA Swift Audubon, pp 8.5x44 BWCF Swift Ultra-Lite, pp 7x42 ZCF Swift Ultra-Lite, pp 8x32 ZWCF Weaver Grand Slam, rp 8.5x45 Weaver Classic, rp 8x42 Zeiss Classic, rp 8x30 B/GA Zeiss Classic, rp 7x42 B/GA Zeiss Victory, rp 8x40 |

328 430 330 368 328 399 330 360 420 390 325 280 330 394 315 366 393 461 405 330 360 393 365 420 330 393 360 340 390 390 408 336 430 367 436 314 332 405 450 405 |

19.5 28.0 25.0 20.6 24.0 31.0 30.1 25.0 29.0 21.5 26.5 23.3 31.4 31.4 19.9 22.0 25.4 21.7 30.0 34.6 22.2 20.3 16.8 20.5 32.0 21.2 26.5 23.0 18.0 28.9 19.0 26.8 24.6 21.0 19.6 29.0 23.6 20.5 28.2 25.1 |

$1,585 650 547 239 684 396 502 510 280 610 721 995 995 1,045 563 384 304 439 529 1,695 957 731 449 459 799 655 250 520 600 1,499 866 767 570(790w/ED) 430 425 529 404 1,000 1,150 979 |

Next: More Choices in Binoculars (coming soon)

Prev: What is Good Glass?